When Marty Sklar retired on July 17, 2009, the 54th Anniversary of the Disneyland Park in California, his title was Executive Vice President and Ambassador for Walt Disney Imagineering. After 53 years of working as a Disney Cast Member, Sklar received a tribute window on Main Street USA in Disneyland – the place where he began his Disney career, one month before opening day of Walt Disney’s original theme park.

Marty Sklar’s career with the Walt Disney Company progressed from Staff Writer to Vice President of Concepts and Planning, and then to President of Walt Disney Imagineering. He was directly involved in the design of Disney Park attractions such as: The Enchanted Tiki Room, it’s a small world, Carousel of Progress, and Space Mountain to name just a few. He was also the only Disney Cast Member who participated in the opening of all 11 Disney Theme Parks, and he was inducted as a Disney Legend in 2001.

Marty Sklar was one of the invited keynote speakers of the DIS Unplugged appearing at our December event (DIS-a-palooza), and agreed to sit down for an exclusive interview to share his experiences working with and for Walt Disney, both the man and the company.

Image: (July 17, 2009) Marty Sklar, Executive Vice President and Walt Disney Imagineering Ambassador holds his tribute window at Disneyland in Anaheim, Calif., on the 54th anniversary of the opening of Disneyland. (Paul Hiffmeyer/Disneyland)

Click here to listen to the complete interview with Disney Legend Marty Sklar.

Note: The recording posted here is a backup file because of technical difficulties that resulted in the loss of the original audio. We apologize for the diminished sound quality, but assure the listener no loss of content from the interview.

Dave Parfitt: Fellow Disney Legend Jim Cora – retired President and Chairman of Disneyland International – described Marty Sklar in the following way, “He understands the Disney way because he learned it at Walt’s knee. He is the keeper of the keys, the conscience, the Jiminy Cricket for the organization.”

Thank you for joining us, Marty. It’s truly an honor.

Marty Sklar: Oh, it’s my pleasure, Dave.

DP: When you started with the Walt Disney Company in 1955, you were a college student at UCLA, and editor for the college newspaper – the Daily Bruin. Could you describe how you were recruited to create a tabloid 1890’s style newspaper, the Disneyland News that was sold on Main Street?

MS: Yeah, someone had recommended me to Card Walker, and Mr. Walker called me at my fraternity where I was living at UCLA, and I didn’t even return the call because I thought one of my fraternity brothers was playing a trick on me – nobody had the name “Card”. Well, I later learned it was E. Cardon Walker, and he was the head of marketing for Disney at the time and much later the CEO of the company. Fortunately, Card Walker called back, and asked me to come in for an interview.

It turned out that Walt wanted someone to put out a tabloid newspaper, 1890’s style, on Main Street at Disneyland, and they hired me to do that job. I went to work one month before Disneyland opened. I went to work in June of 1955, and two weeks after I went to work I had to present the concept to Walt Disney – The, Walt Disney.

DP: And so you were a college student at the time.

MS: I was a college student, had never worked professionally, and believe me I was scared as hell. I’ve told people many times since then, the good fortune is that Walt liked what I presented, and that’s why I lasted 53 or 54 years at Disney.

Image: This is a rare color image of opening day taken outside the Main Entrance of Disneyland on July 17, 1955.

DP: What do you remember from Disneyland’s opening day: July 17, 1955?

MS: The opening day was a madhouse. There’s so many stories about that. They invited some 15 or 16 thousand people, and over 30,000 showed up because of counterfeit tickets and people who rushed the gate and all kinds of stuff. It was a madhouse, but I worked part of the day in… the way the television show worked, they went 55 minutes live and then they gave it to the local stations – KABC. It was on ABC by the way, and Disney had nothing to do with ABC at that time. I was working with the local people for most of the day.

The second half of the day I was out in the park, and I remember distinctly Fess Parker (Davy Crockett) riding up to me on his horse and seeing my name tag and saying, “Marty, get me out of here before this horse hurts someone!” Laughs…

It was that kind of day. It was pretty wild. I was living in Long Beach, which is about 20 miles from Anaheim. Between my house (I was living with my parents), and between the park and that part of Long Beach there was hardly anything. There was open land practically. Except for a few bars along the way, and I think I hit every one of them on the way home.

DP: Doing what a good college student should be doing at that point.

MS: Absolutely.

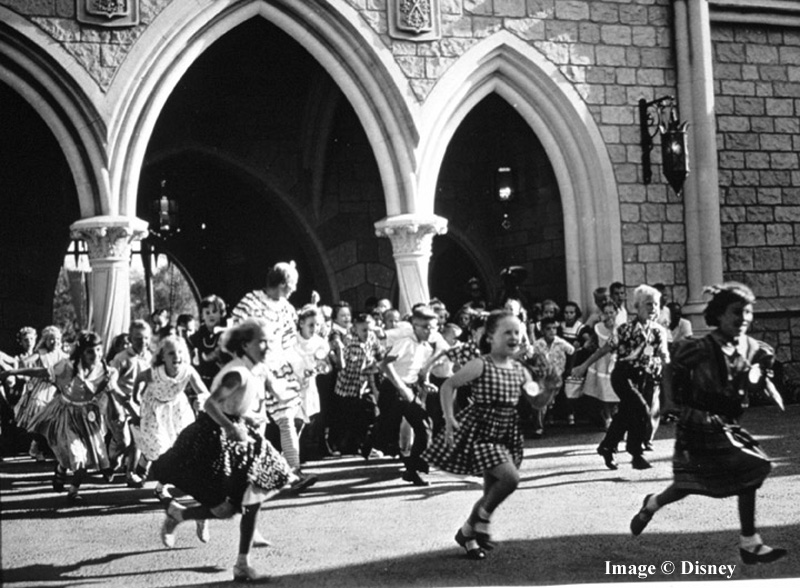

Image: Hundreds of children run through Sleeping Beauty Castle after the long-awaited lowering of the drawbridge into Fantasyland on July 17, 1955.

DP: After graduating from college, you came back, you worked for Disney, you wrote for Walt Disney himself for about 10 years, and really helped him articulate his vision that he used in publications, television, and film. What was it like working side by side with Walt Disney?

MS: Well, it was a unique opportunity for me at a young age like that being exposed to Walt. I was the kid at Imagineering at the time with so many fabulous veterans: Marc Davis, Claude Coates, John Hench, Herb Ryman, X. Atencio, Rolly Crump, Blaine Gibson, Bob Gurr… you know they were all my mentors in so many ways – especially John Hench. John and I became very close over the years, and it ended up with the two of us being the key people in creating Epcot. But in those days I was really learning the business at the foot of all those wonderful people.

And I had an opportunity early on to write some things that Walt wanted to do that he hadn’t had the opportunity before Disneyland opened. One was to do a booklet about Disneyland that could be given to potential sponsors. There were two companions to that booklet. One was a booklet we did about Liberty Street – because Walt wanted to do a Liberty Street in Disneyland, and the other was called Edison Square. He wanted to do an area of Disneyland called Edison Square. Both of those things came to fruition many years later. Edison Square as the “Carousel of Progress”, and Liberty Square of course in the Magic Kingdom here at Walt Disney World. So I had the opportunity to write and put those pieces out, and then I started writing pieces for Walt for the souvenir guides that were sold in the park and ultimately for annual reports.

I used to work with both Roy Disney senior and Walt Disney – actually, the annual reports, because they were financial documents, were Roy’s project. I would sit down with Roy, and he would tell me what he wanted to do. It was my job with a couple of great artists, Bobby Moore who did all the marketing art at the time for the studio and Norm Nocetti who was a great artist, and we did the annual report for about 3 or 4 years and changed the way Disney did those annual reports. Previously, in the early 60’s, the reports had been very dry, financial documents, and we gave each one of them a theme and a story.

Image: Walt Disney’s Carousel of Progress in Magic Kingdom’s Tomorrowland

DP: And put some creativity in it.

MS: Yeah, they became sales pitches for the company in many ways. We’d take our cue from what Roy wanted to do, and then I would figure out how to write Walt’s copy to go along with that. Then we’d take it to Walt, and, it wasn’t his primary focus, but I always got input from him and my red pen marks. Laughs…

DP: I was going to ask what type of critique and feedback would you get from Walt Disney?

MS: Well, you always got feedback from Walt on whatever it was, and in his own hand writing. He was very articulate with his notes, and if you ever have a chance in the archives at the Disney Studios to see some of the scripts for films you’ll see Walt’s notes all over them. He was into every project he did, and he knew where he was going and what he wanted to accomplish.

DP: Very hands on…

MS: Absolutely, which was great, it was a learning experience for me at the time.

DP: You were then hand-selected by Walt Disney to be part of the team to develop shows and pavilions for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City. Some of those attractions included “it’s a small world”, “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln”, “Magic Skyway”, and “Carousel of Progress” what at that time was “Progressland”. At the time when you were working on those projects developing those plans, did you have a sense or realize what an impact those would be for the future of Disney Parks?

MS: You know we really didn’t because we were so busy just trying to do those shows. Because we started out with working with GE and then Ford and then the State of Illinois, and then a year before the fair opened UNICEF came to Walt and asked to do a pavilion about the children of the world. Literally, within 11 months from first idea to opening we did “it’s a small world”. So we were just running as fast as we could and trying to get everything done. In retrospect, you could see exactly what Walt was doing. He really wanted to grow Disneyland, and use other people’s money to do that – in the best sense of the word. The way he chose to do it was to try to get the companies to bring the attractions from the World’s Fair to Disneyland. For the first time they had to put a value on Walt Disney’s name, and they decided that for the course of the Fair that just his name rights was $1 million dollars. Walt was so interested in, not the money, but, rather, getting those companies to come into Disneyland he said to them – if you come into Disneyland the million dollars is your down payment. It’s your first part of your payment for being in Disneyland, and GE decided to do it and Ford decided not to do it. The company owned “it’s a small world” from the beginning. The Lincoln show was in Disneyland the second year of the Fair. We opened it in Disneyland in 1965.

It’s a small world, we actually built it in Burbank, even built the troughs that the boats went on, and all of that was shipped to New York – because, we only had 11 months. You couldn’t go around looking for vendors in New York. You just had to get it done where you could. So all of that, the sets, the figures, the troughs, everything moved back to California and when “it’s a small world” opened at Disneyland in 1966 that was straight out of the World’s Fair.

The other thing Walt was doing – is at the time, Disney films didn’t do as well in New York City as they did in other parts of the country. So he was sort of testing the water for building a “Disneyland” somewhere else in the country. So the World’s Fair was kind of a stepping stone to Florida.

Image: Walt Disney “meets” some residents of the ‘it’s a small world’ attraction at Disneyland in California, during construction in May, 1966.

DP: That was exactly what I was going to ask, if Walt was conscious of that decision; if it was cognizant in his mind that he was testing the waters on the East Coast so to speak.

MS: Yeah, absolutely. In fact, he had been approached by RCA to do a project in south of Florida, and ultimately decided not to, but even during the World’s Fair, they were buying the land for Walt Disney World.

DP: After the World’s Fair, in late 1966, you wrote a script for Walt Disney for a short, 20 minute, film designed to communicate his vision for EPCOT – the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow. Unfortunately that turned out to be Walt Disney’s last filmed appearance. Could you talk a little about the production of that film with Walt Disney?

MS: Well, I had the opportunity to work with two wonderful people, who, at the time, were doing all the park shows for the television series. That was Ham Luske and Mack Stewart. Ham was one of the stars of 1930’s animation. I think he is best known for “The Tortoise and the Hare”. He was a director in animation and involved in doing television for the park shows like “Disney Goes to the World’s Fair” and the shows about Disneyland. They were wonderful people to work with; I loved working with them.

We really didn’t have a lot of materials to tell that whole story. So we were borrowing from lots of different developments to make that 20 minute film that we did. The whole purpose of the film was to communicate about Disney and Walt’s vision for Epcot. It was designed to help sell the Florida legislature on creating what was originally called the “Reedy Creek Drainage District”, and ultimately the name changed to Reedy Creek Improvement District which exists today. The whole idea was Walt would travel around to the great laboratories of American industry, the GE labs, the Sarnoff labs that were RCA, DuPont, Ford, and IBM. Every time Walt would come to one of those labs they’d trot out the latest thing they were working on. Quite often they’d have nothing to do with products they were selling, and Walt would say, “When can I buy a product based on that technology?” They’d look at him and say, “We don’t know if the public is interested in this.” So Walt came to think that he could be a middle-man between industry and the public – showcasing and demonstrating products and new ideas. Really that’s how Epcot started to evolve. He got a lot of work done on ideas for how to build a community.

Image: Spaceship Earth is the visual and thematic centerpiece of Epcot at Walt Disney World Resort

MS: I remember any number of meetings with him (Walt) about the script, and I still have about 8 pages of notes from those meetings. He was constantly saying to me, “I want to make sure that we meet the needs of people in this project.” That was a real focus.

I think a lot of Walt’s thinking came from experiences that he had. Not only visiting those laboratories of American industry, but I remember one story he told me about he and Mrs. Disney babysat for Diane Disney Miller and Ron Miller’s children. They went off on the weekend, and it happened that the trash trucks – they lived on a street where there was an alley behind the house – and about 6:00 in the morning the trash trucks came down the alley tossing the trash cans in all directions. Walt started saying, “Why isn’t there a better way to collect trash?” That led to the AVAC system we installed here at Walt Disney World from the beginning – because we were looking for something that would meet the needs of people.

DP: It goes back to the beginning of Disneyland too, where you hear the stories of Walt wanting a place where he could take his children.

MS: Absolutely, in fact he made that very clear that Disneyland came from his experiences of taking Diane and Sharon, his two daughters, to amusement parks, particularly a little amusement park at Beverly Boulevard and La Cienga Boulevard, where the Beverly Center is now – a big development in Los Angeles. He said he would have to sit on the park bench and eat peanuts or popcorn while the girls had all the fun. He started thinking, why isn’t there someplace where children and their parents can have fun together?

If you think about Disneyland, there was only one attraction, and it came the second year called Jr. Autopia, and it lasted one year and Walt took it out. The reason was because everything else in the park, and this goes for today, are things that adults and children can do together – the Jr. Autopia, only little kids could go on. That was a throwback to something that had frustrated him with his own daughters, and so he wanted everything to be participatory, to be story-based, but things that adults and children could do together.

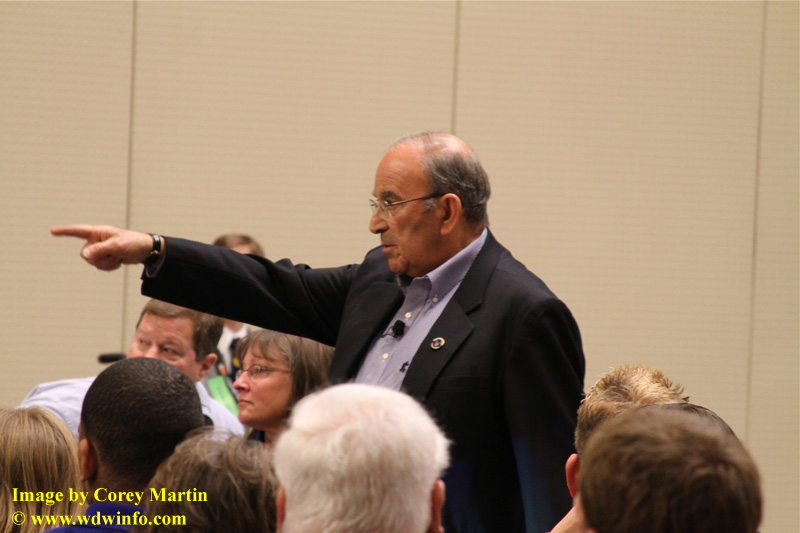

Image: Disney Imagineering Legend Marty Sklar delivers a seminar titled “Just Do Something People Will Like!” on December 11, 2009

DP: Getting back to the idea of Epcot being a solution to the urban crisis to the modern city – a lot of architects today, if you look at the readings, say “look at Disneyland”, Disneyland is a model of urban planning.

MS: I think one of the things that made us proudest after Walt Disney World opened was David Brinkley, who was then at NBC, came here and did a piece for his nightly news where he said that this was the greatest piece of urban development in the country. A lot of people felt that way because we separated people from their cars and put them in other kinds of transportation. We had energy systems, trash collection systems, electricity systems, so many different things that we tried to carry out the philosophy even if it wasn’t the city that Walt had envisioned. In fact, I wrote the preamble to the Epcot building code, and I’m not an engineer in any respect. But the whole idea was to express the philosophy, and the philosophy was how do we encourage American industry to develop and demonstrate new systems and new technologies where the public could see it.

DP: In 1974, you became the creative leader for Walt Disney Imagineering. The Walt Disney World Resort had been open in Florida for about 3 years, and the current Walt Disney Company CEO E. Cardon “Card” Walker, who you mentioned earlier giving you your first interview, he calls you up and one of the first things he asked is “What are we going to do about Walt’s idea for EPCOT?” How do you react to that phone call?

MS: I think I fell off my chair. Laughs… You know, this was a daunting moment for me or for anybody to pick up a big, big idea like Epcot and do something with it. Well, we decided that the only way we could get our heads around it was to hold a series of conferences here in Florida: we had one on energy, we had one on health, we had one on transportation, we had one on food, and probably a couple of others. We invited people that we researched from academia, from big companies, from government, and we discussed what kinds of communication there should be to motivate and inform the public – all done under the guise of “fun”. It was very interesting because these people came from all kinds of pedigrees, very smart, lots of big thinkers, and after every meeting, they would come back to us and say, “Look, the public doesn’t trust what industry tells them, they don’t trust what government tells them, but they all trust Mickey Mouse. You people have a role.”

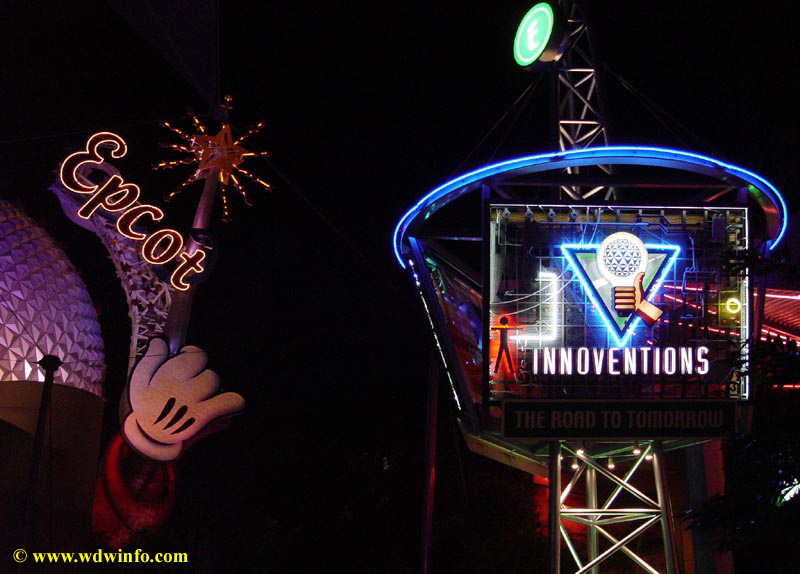

Image: Innoventions East in Epcot’s Future World

MS: We developed the whole idea that we were going to communicate the best information that we could have in an entertaining way, and to do it where we knew you could only have what I called, as I talked to our staff at Imagineering, “Look, what we’re doing is turn-ons. We want to get people excited about knowing more, and at the same time having fun while they’re doing it. So don’t think you have to tell the whole story here.” In fact, when we opened Epcot we had an information center where you could reach out to what was happening in energy all over the country, what was happening in food in different places in the world, and we had only one criterion. This was long before the internet. That would have been easy if we could have had people come in and use their computers, but they didn’t exist. What we did was we found sources that we felt people could reach out to, and we made a deal with them that if we listed them in our brochures that they had to respond within 10 days to any inquiry that came from the public. It worked out pretty well. It was an adjunct to the entertainment – to the big pavilions. It’s kind of like what has become of Innoventions. Innoventions is terrific today in Epcot because it allows small ideas that you can’t build a whole pavilion for, and you can demonstrate and test different things for the public.

DP: Very hands on, very interactive…

MS: So I think that in a way that has reinforced what we started out to try to do in Epcot.

DP: Was there ever any consideration when you were first developing this idea, or when Card Walker approached you with Epcot, of going back to Walt Disney’s original plan and making a living working community?

MS: Well, by then of course Walt Disney World was established as a resort destination. No, I don’t think so – the company, Disney, wasn’t big enough and strong enough at the time to take something like that on. From my standpoint, I don’t think it was possible without Walt Disney. Because Walt Disney could walk into any big company and the chairman or CEO would welcome him and listen to his story. Listen to his pitch, if you will. We had nobody like that. There isn’t anybody that can do that kind of… not only at Disney. Walt had the reputation, and the World’s Fair, he was the star of the World’s Fair. The four Disney shows were four out of the top 5 shows of the Fair. So Walt was, with some of those companies, with some of those chairmen, he was a god.

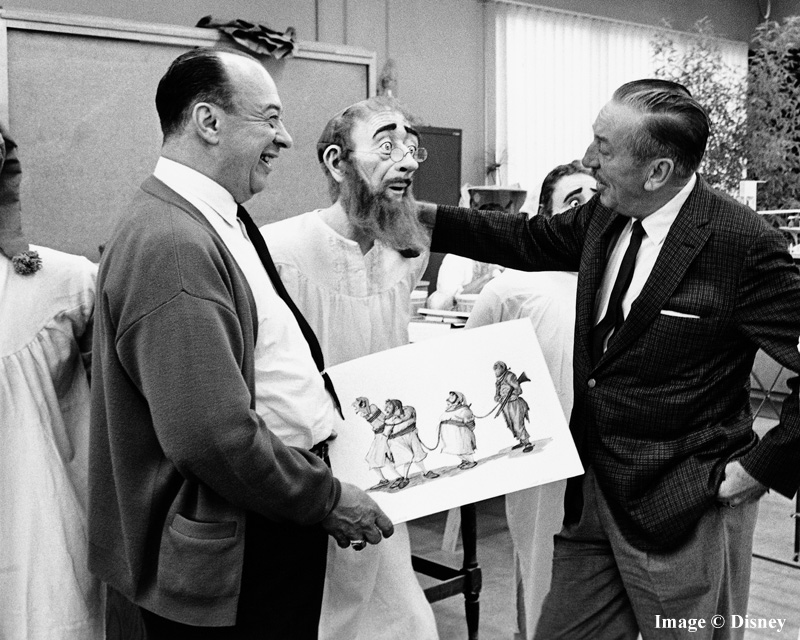

Image: Disney Imagineering Legend Marc Davis (L) looks on as Walt Disney examines their lifelike creation; an Audio-Animatronics figure created for Pirates of the Caribbean which opened at Disneyland in Anaheim, Calif. on March 18, 1967. It was the last Disneyland attraction personally supervised by Walt Disney.

DP: Sounds like he was not only a person who had the intellectual, the genius, but he also had the charisma to get people to believe in his idea as well.

MS: You talk to any of my colleagues – I was just on a panel at IAAPA (the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions), their annual conference just happened to be in Las Vegas, and I served on a panel with Richard Sherman, Blaine Gibson, Bob Gurr, and Buzz Price – the five of us, actually. We all had the same message that Walt inspired all of us, and made it very clear to all of us that whatever we had done before was never going to be good enough again – because he was moving on. So we had to get better every time we did a project, and the parks reflected that – the growth of Disneyland, the new things that were being done, the planning for Walt Disney World, all of those were giant steps forward as we went along.

By the way, going back to your question about the World’s Fair, the World’s Fair was a big watershed in this respect. Before the Fair, the capacity of attractions was not very significant, but once that water ride for “it’s a small world” was invented where you could carry 3,600 people an hour in a boat ride, that made the “Pirates of the Caribbean” possible.

DP: Because before that time “Pirates of the Caribbean” was on the drawing table as a walk-through.

MS: As a walk-through, and after we did “it’s a small world” for the Fair the first thing Walt did was come back and say “we can’t do a walk-through, we can’t handle enough people.” The operating people were, of course, very much against walk-throughs. Because they realized they could handle only six or seven hundred people an hour, and that wasn’t good enough anymore. So here was an opportunity to be able to tell a story, in a dramatic fashion and at the same time handle over 3,000 people an hour and that was a major, major leap forward.

Image: Disney Imagineering Legend Marty Sklar answers questions from DIS Unplugged fans on December 11, 2009

DP: I was able to read some of your comments from the panel you had mentioned, the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions discussion panel you were on. I saw a quote that was attributed to you where you said, “Walt was the greatest casting director that ever lived. He knew not to pigeon-hole anyone. You never know what you might find when you give somebody an opportunity.” It really seems that was true for your career as well – hired as a college journalism student and eventually ending up as President and then Principal Creative Executive of Walt Disney Imagineering. So what advice would you give to those young people out there today who have the dream or desire to become an Imagineer?

MS: Well you got to do it; you got to work at it. I’ve told young people this for years, probably answered hundreds of letters over the years, learn as much as you can about as many things as you can when you’re young, and try a lot of different things. Because you never know what you’re going to find that you like doing and what you’re good at. If you just say, “Well, I’m going to be such and such”, you’re pigeon-holing yourself. While you’re young, especially, you should try as many things as you can, have as many experiences as you can, so that you can really figure out what you like to do, and how you want to spend all those years of life that are ahead of you. I think that’s really important. You never know what education you learn in different subjects how that’s going to pay off in the future.

DP: Reflecting back on some of my advisors and mentors and college professors, I think the ones that always made the biggest impact on me were the ones that pushed me to do more than I thought I could accomplish. It sounds like that is exactly what Walt Disney was doing with his team as well.

MS: Buzz Price who did the site study for Disneyland and Walt Disney World and worked on a lot of the economic feasibility studies he said it right. He said, “You could say to Walt ‘yes, if’ but you could never say ‘no, because’.” Because Walt would find somebody that was willing to take a risk and try whatever it was that you would think wouldn’t work. I think it’s really good advice. Because Buzz Price said, “no, because” is the language of a deal killer, and “yes, if” is the language of somebody that wants to make the deal. That’s what Walt wanted, he wanted to make the deal all the time.

Walt didn’t really care what your role was supposed to be. He had something in mind for you that you never… I know in my case, I was sitting having coffee… we had a Hills Brothers coffee shop on Main Street in Disneyland, and this was about 1960. Walt came in, and I was sitting with Eddie Meck who was the director of Disneyland and my boss. I wrote all the publicity and Eddie planted it in the media. Walt sat down and he turned to me after a while and said, “What are you doing, Marty?” I said, “I’m doing all the publicity with Eddie.” Walt looked at Eddie and said, “We’re going to have to give you something more important to do.” Laughs… and I don’t know what he’d seen in me. As I said, I had the opportunity to write a number of different things for him, and he had decided that I was going to be doing something else – as he saw the need.

Image: Disney Imagineering Legend Marty Sklar addresses DIS Unplugged fans on December 11, 2009

MS: I think about X. Atencio who had never written a script in his life, and Walt sent him over to Imagineering and called him one day and said “X., I want you to write the script for ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’.” X. said, “I don’t know how to write a script”, and Walt said, “Well, try.” X. came back and said, “How about a song? I have an idea for a song. Yo ho, yo ho, a Pirate’s Life for Me.” You talk to Richard and Robert Sherman and they just idolize the opportunities they had to work with Walt Disney, developing story, and having the opportunity to do things they never thought they’d be doing. They were all over the place.

Blaine Gibson was our chief sculptor at Imagineering. He was an animator, and that’s all he wanted to do. He was a good animator, but not one of the greats. Walt saw an exhibit he did at the studio library. Blaine had done some sculpture to go along with somebody’s art. Walt put that in the back of his mind, and one day he called Blaine and he said, “I want you to be my sculptor on Disneyland.” Blaine said, “No, I want to do animation”, and Walt said, “No, no I want you to do this.” Blaine, to this day, thanks Walt for 30 years as the greatest sculptor who ever worked in our business.

Bob Gurr – I always kid Bob. He designed all the vehicles for Disneyland, and he designed the first Lincoln figure. I said to Bob, “Why didn’t you tell Walt when he wanted you to engineer this, why didn’t you tell him you don’t know anything about engineering?” Bob said, “No, no, you don’t tell Walt you didn’t know, you found out [how].”

DP: That’s great. I think a great story, and a great way to end. Again, I’d like to thank Disney Imagineering Legend Marty Sklar for taking the time to speak with us, and I am very much looking forward to your presentation. This is David Parfitt signing off for the DIS Unplugged, thanks for listening.

MS: Thank you David.

Leave a Reply